Working in social networks to find solutions

Aliens have arrived on planet Earth. There's only one way to handle this situation: you and a partner must work together to compose a musical tune that will please the extra-terrestrial visitors. In doing so, you're going to help researchers answer questions about how people come up with optimal solutions to complex problems together.

Here’s what happened in the study “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”: participants joined the study in sessions of exactly 16 people each. After signing a consent form, everyone was seated at individual stations in a computer lab, upon which the researcher started to give instructions. “Space ships are approaching the Earth, and their intentions are unknown. Apparently, they only communicate through musical melodies.”

On their computers, participants were shown a screen with an image of the approaching spaceships, a few piano keys, and a chat interface. They were paired with another player, and, using the chat-function only, they had two minutes to figure out what melody to compose as a message to the aliens. The first attempt to create a tune was pure guesswork, as no information was given about what might make the aliens happy or unhappy. Once the message was composed and sent, participants were presented with feedback, consisting of a score between -25 and +40, and the image of an alien who was either pleased or – if the score was sufficiently low – mortally offended.

Then a new round begun. Participants once again had to compose a melody in pairs – this time knowing a little more than before. Via the chat function, they could share their thoughts and ideas, and work towards finding a better solution than before.

With each round, participants had to work together in pairs to try to get a higher score. With five possible notes to choose from, and the melody itself being four notes long, there were a total of 625 possible outcomes. Only one of them would get the maximum score of 40 points.

This went on for an hour, and then the experiment concluded. For their participation, each person was rewarded 100 DKK.

But what was the point of all this? What did the researchers achieve?

The impact of social network patterns on finding known and unknown solutions

Once the experimental part of a study is over, the researchers are left with a great deal of information, or data. Their next step is to analyse these data to find patterns and gain insights, which can take a long time. Finally, the results will often be published, for example as an article in a scientific journal. Writing and editing a research article also takes a good while. So from the time an experiment has concluded and until results are ready to be published, many months can have passed. In the case of this study, the analysis is not complete. However, the data have yielded a few preliminary observations. These observations may change upon further analysis, but they are presented here as an example of what kind of results can come from a study such as this.

First, it’s important to know that not all the sessions happened the exact same way. By varying the conditions of the experiment, researchers were able to compare different treatments and deduce results on this basis.

One thing the researchers investigated was how performance was affected by the type of network the participants worked in. In other words, if people worked together in specific patterns, how did this change how well they did? Was it easier to get a high score if you worked with a lot of people, or just a few?

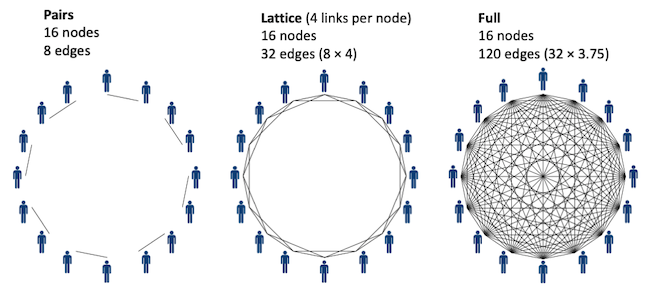

The researchers considered three patterns: pairs, lattice, and fully connected networks. In the first pattern, participants worked with the same partner throughout the experiment. In the second, they worked with four different partners, meaning that each round, they were randomly paired with another person from their group. Finally in the last pattern, participants were randomly paired in each round with another person from the entire group of 16 people in the experiment.

The purpose of this investigation was, among others, to see if there is an optimal social structure for finding solutions. The researchers had two hypotheses about this: 1) that repeated interaction with the same partner improves performance, and 2) that more connections give access to more information and improves performance. As few connections – e.g. working with the same partner the entire time – is opposite to working with many connections – i.e. multiple people – these two hypotheses seem to represent a fundamental trade off. Preliminary observations suggested that pairs performed worse than both lattice and fully connected networks.

Another variable the researchers looked at was what happened if participants knew what the maximum possible score was. Consider that you were part of the experiment, and by pure luck, you got a 40 point score in the first try. If you didn’t know this was the maximum score possible, you would continue to search for a better solution. However, if you knew it was the maximum score, you wouldn’t need to explore your options further. Thus, having knowledge can be expected to influence how participants search for solutions. This seemed to be supported by preliminary results, which suggested that participants did more to explore their options when the maximum possible score was unknown. The researchers also saw indications that if participants didn’t know the maximum possible score, the lattice pattern of connectivity gave the best overall performance.

What was the point of the aliens?

No point – except to make the experiment interesting and motivating for participants. There’s no reason behavioural experiments should be dull. To the contrary, if people are bored, then this can negatively affect their effort. But if they are composing music to make alien invaders happy, they might have fun while helping researchers get new insights into connectivity, collaboration and complex problem-solving. And that’s a win for the human race.

About the experiment

- "Close Encounters of the Third Kind" ran intermittently between December 2016 and December 2018.

- A total of 481 people participated in the experiment.

Researchers behind the experiment

- Riccardo Fusaroli (School of Communication and Culture – Semiotics, Aarhus Universitet)

- Dan Mønster (Department of Economics and Business Economics, Aarhus Universitet)

- Kristian Tylén (School of Communication and Culture – Semiotics, Aarhus Universitet)

- Andrea Baronchelli (School of Mathematics, Computer Science and Engineering – Mathematics, City University of London)