How to make selfish people cooperate

Signaling expectations to each other can increase cooperation among would-be free-riders. Researchers shed light on how selfish people can be nudged into cooperating as much as cooperative people when they are able to signal their expectations and know that the other participant is also selfish. However, their intention seems to be only to benefit their own material self-interest in the end.

We all know the kind of person who benefits from the group’s effort without contributing anything themselves. Let it be that lazy member of the study group or that roomie who does not want to share food but gladly takes yours. On a societal level these free-riders are persons who enjoy public goods while paying little or no taxes.

Researchers of this study investigated how signaling expectations and getting information about the other player in a public goods scheme affected their willingness to cooperate. These conditions turned the most selfish free-riding players into the most cooperative players in the game.

Expectations and knowledge about the other player boost cooperation among selfish players

In the study the researchers find that two conditions activate cooperation in a social dilemma among selfish subjects:

- Common knowledge that the other player is selfish

- Exchange of mutual expectations

The two conditions are both necessary to dramatically improve cooperation. The exchange of mutual expectations is in itself not a sufficient condition for selfish players to cooperate – actually, it is counterproductive to cooperation if there are no common knowledge that the other player is also selfish.

Michiru and colleagues tell: “We suggest that the results can be explained by what Robert Morton (2002) calls ‘solution thinking’, which is a generalized form of team reasoning. Since there is no one to free-ride on, the only way to make money is to cooperate, but in order to cooperate the selfish player needs to be confident that the other player is thinking and expecting the same”.

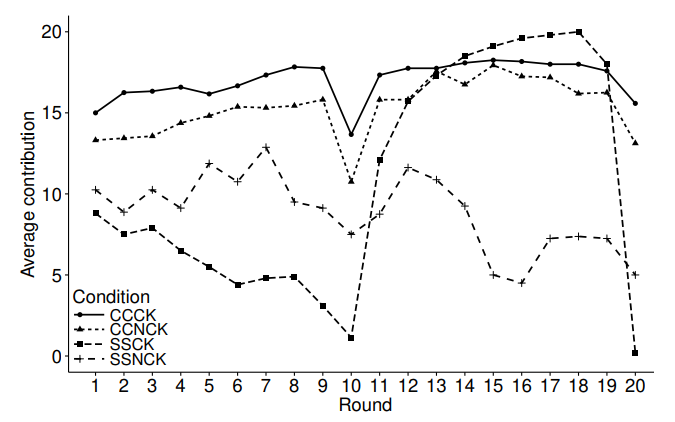

The variation in cooperation among the players is illustrated in the following figure:

Note: CCCK =Conditional Cooperators, Common Knowledge, CCNCK = Conditional Cooperators, No Common Knowledge,, SSCK = Selfish Subjects, Common Knowledge,, SSNCK = Selfish Subjects, No Common Knowledge. In rounds 11-20 participants stated their expectations.

As can be seen in the figure of average contributions by round, the selfish players cooperate more with each other than other player types until the last round, when the curve drastically drops.

About the experimental procedure

All participants in the study began by playing a one-shot public goods game (with the strategy method) in an online survey. Based on this survey the participants were identified as either ‘Conditional cooperator’, ‘Selfish’ or ‘other type’. Hereafter the participants were invited to the lab and paired with another participant of their type. They played a public good game in two conditions: with and without information about the other player’s behavioral type.

Possible solutions to social dilemmas in our society

“These kind of public good experiments are relevant because they simulate many real situations of social dilemmas that might be improved for better social welfare. More specifically, this study focuses on the mechanism through which homogeneous free-riders can achieve cooperation” Michiru says.

Although public good games are a kind of analogy to one of the most fundamental questions about the organization of our society, there is a long way from the lab to real life situations. However, results from studies like these can help shed light on possible ways to work against the free-rider problem:

“Punishment, a popular institution used in labs, is not possible in many real-life situations. Grouping and communication are relatively easy to achieve and therefore might be a cheap way to encourage volunteer contributions to public goods in real life settings” Michiru adds.

Are Danes less selfish?

This was Michiru’s first experiment in Denmark and he had one challenge that might be related to the Danish culture:

“A more specific challenge was to get enough participants for this study. We wanted more selfish participants but fortunately—and unfortunately for us—Danish students tend to be very cooperative!”

The article is called "Making good cider out of bad apples - Signaling expectations boosts cooperation among would-be free riders" and was published in 2018.

About the experiment

- The experiment was called ‘Study on Economic Decision Making’ and was conducted in COBE Lab in March 2015

- 227 people participated in the online study, and 50 people participated in the lab session

The short story

- The most selfish people who normally tend to free-ride are nudged into cooperating as much as cooperative people

- Researchers investigated the effect of signaling expectations and receiving information about the other players in a repeated public goods scheme

About the researcher

Name Michiru Nagatsu

Background and job role I have a multidisciplinary background but basically I’m a philosopher of science focusing on economics and psychology in particular.

Main areas of research Philosophy of economics, human rationality and sociality

Other researchers related to the study

- John Michael (Warwick)

- Karen Larsen (Helsinki)

- Mia Karabegovic (CEU, Budapest)

- Marcell Székely (CEU, Budapest)

- Dan Mønster (Aarhus)